The Swedish Mini-Berkshire You've Never Heard Of -- But Should Own for the Next Decade

When I analyze a business, I don't begin with its chart. I begin with the owner's question: if I could buy the entire company at today's price and hold it for a decade, would I? That simple lens, which Buffett has used for decades, forces you to strip away market noise and focus on the essence of the enterprise.

Teqnion AB, a small-cap industrial holding company listed in Stockholm, is one of those names that quietly passes this test. It doesn't make headlines. It doesn't live in flashy sectors. But behind the modest market cap sits a compounding machine: a diversified group of niche industrial companies, all profitable, all throwing off cash, overseen by a founder-CEO with real skin in the game.

If you squint, the strategy looks like a miniature Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A) (BRK.B) or a Scandinavian cousin of Constellation Software (CSU). Buy small, profitable, overlooked businesses in obscure niches. Leave them to run independently. Recycle the cash into the next acquisition. Done consistently, this creates one of the most powerful compounding engines in investing. The only question that matters is whether today's price offers enough safety to ride that engine for the next decade.

Understanding Teqnion Like an Owner

On the surface, Teqnion is a holding company. But that label doesn't capture the essence. Beneath the legal structure is a decentralized group of more than thirty small businesses. These subsidiaries operate in niches ranging from defense scoring systems to cremation furnaces to foldable electric wheelchairs. Each one is small enough to be ignored by larger competitors, but significant enough to dominate its niche.

Customers are overwhelmingly B2B. Municipalities rely on Teqnion subsidiaries for road safety equipment. Defense clients turn to its units for training systems. Healthcare distributors purchase its mobility devices. Laboratories depend on its instruments. These are not impulse purchases. They are specialized products with reputations built over decades, where reliability and expertise matter more than squeezing out a few percent on price.

Revenue comes from these subsidiaries' day-to-day operations, but growth is powered by two levers. Organic growth tends to be modest, a few points above inflation, reflecting the mature markets these companies serve. The real acceleration comes from acquisitions. Teqnion targets companies with annual sales between SEK 25150 million, roughly $215 million, often family-owned, usually overlooked by bigger players. The sweet spot is to pay less than five times EBITA, a level that almost guarantees an attractive return on invested capital once cash flows are reinvested.

Margins are steady. At the group level, EBITA typically falls between 9%-12%, with net margins closer to 6% to 9%. These aren't venture-style numbers, but they are durable, cash-converting margins that compound over time. Because the businesses are capital-light assembly, distribution, or specialized manufacturing free cash flow conversion is consistently high.

The model is decentralized to its core. Headquarters does not meddle in daily operations. Subsidiaries keep their identity, employees, and culture. What Teqnion provides is capital allocation, strategic oversight, and the promise of eternal ownership. That promise alone is a moat in acquisition markets, as many founders prefer to sell to a permanent home rather than a private equity fund looking to flip in five years.

The Moat Is in the Model

Each subsidiary carries its own small moat brand recognition in a narrow field, technical expertise that newcomers can't easily replicate, regulatory approvals that take years to obtain. None of these alone would excite investors hunting for dominant platforms. But combined under one umbrella, they create a resilient portfolio.

The true moat, however, lies at the group level. Diversification is the first layer. Teqnion's thirty-odd companies operate in different end markets, smoothing results when one sector weakens. That diversification alone provides resilience. The second layer is reputation with sellers. By positioning itself as a permanent, respectful buyer, Teqnion has created a pipeline of deals that competitors cannot easily replicate. For founders who want their legacy protected, Teqnion is often the preferred exit.

Capital allocation discipline is another layer. By consistently paying 4-6 times EBITA for companies that the stock market values at 15x within Teqnion, management locks in value creation with every deal. That arbitrage is the beating heart of the compounding model. As long as discipline holds, each incremental acquisition is accretive.

And then there is culture. Teqnion's decentralized, entrepreneurial ethos allows each subsidiary to thrive without bureaucracy. Headquarters remains lean, with overhead at barely 1-2% of sales. This culture of autonomy and accountability is not easily replicated by larger, more bureaucratic rivals. It is the invisible glue that makes the model work.

Compared to larger Swedish serial acquirers like Indutrade, Lifco, or Lagercrantz, Teqnion is still small, with just $165 million in revenue. But that small size is an advantage. It can acquire businesses that are too tiny to move the needle for bigger players, allowing it to fish in less competitive waters. The moat, far from being static, is slowly widening as the group grows, reputation compounds, and cash flows recycle into new acquisitions.

The People Running the Show

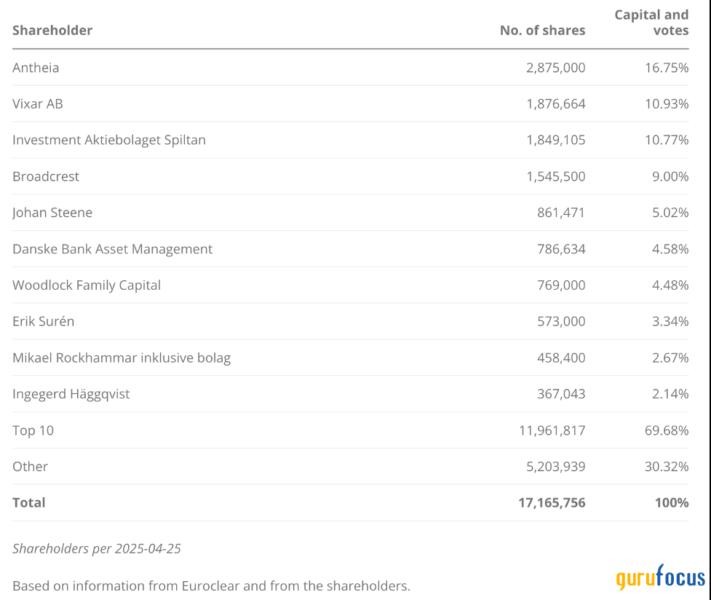

A model like this lives or dies by its stewards. Teqnion was founded in 2006 by Johan Steene, who remains CEO. He is not a hired hand. He is one the largest shareholders, owning over 5% stake in the company, aligning his personal wealth with shareholders. That alignment matters. It ensures capital allocation decisions are made through the lens of long-term compounding, not quarterly optics.

In early 2025, Daniel Ek, the co-founder and CEO of Spotify (SPOT), became Teqnion's largest shareholder, acquiring up to 16.75% through his family office. Spiltan, one of Sweden's most respected long-term investment firms, is also a top owner. This is not hot money. These are patient, aligned investors who think in decades.

Capital allocation so far has been disciplined. Teqnion has avoided the temptation of dividends, preferring to reinvest cash in acquisitions. It has avoided reckless buybacks, waiting instead for math to make sense. Expansion has been steady, not reckless, and always within the bounds of a conservative balance sheet. In years when profits dipped, such as 2024, management acted decisively. Costs were cut, underperforming subsidiaries were merged, and new leadership was installed where needed. The candor with which Steene described 2024 as an F grade year spoke volumes. That willingness to admit failure and take corrective action is precisely what you want in an owner-operator.

The Financial Engine

The numbers tell the story of a compounding engine. Revenue has grown nearly 10x in less than a decade, reaching 1.57 billion SEK in 2024, or roughly $165 million. Net income has compounded at a 31% clip despite the occasional dip, rising from around SEK 14.2 million in 2015 to nearly SEK 125 million in 2023 before falling back to SEK 95.6 million in 2024.

Margins have held within a predictable range. Gross margins hover around 37%-45.4%. EBITA margins typically fall between 4%-14%, reaching 11.3% in 2023 then dipping to 7.85% in 2024. Net margins are 7%-9% in normal years, falling to just over 6% during the downturn.

Returns on equity have averaged above 20% in strong years, dipping to 12% in 2024. Return on invested capital generally sits in the low teens, reflecting the disciplined acquisition multiples. Free cash flow closely tracks net income, with conversion rates averaging nearly 90% in the past three years. In 2024, Teqnion generated SEK 83 million of free cash flow against SEK 95.6 million of net profit.

The balance sheet is conservative. Net debt to EBITDA is around 1.9 times, well under the company's 2.5 times ceiling. Cash sits at roughly SEK 137.4 million, and debt is structured through flexible bank facilities rather than long-term bonds. Goodwill and intangibles make up much of the asset base, as expected for an acquirer, but impairments have been minimal, reflecting sound deal-making.

This is a capital-light, cash-generative business with prudent leverage. It is exactly the financial foundation you want for a compounding model.

The Risks That Matter

No business is bulletproof, and Teqnion is no exception. The most obvious risk is economic downturn. When industrial orders slow, margins compress, as seen in 2024. Another is integration risk. A bad acquisition or too many deals too quickly could strain management bandwidth. Key-man risk is also real. Johan Steene's leadership is central. Losing him without a strong succession plan would hurt.

Competition for acquisitions is intensifying. Larger serial acquirers and private equity funds could push deal prices higher, reducing returns. Expanding internationally introduces currency risk and operational complexity. And like all small caps, the stock is volatile, with liquidity limited compared to larger peers.

These are real risks. But they are not existential. Diversification across thirty businesses, conservative leverage, and a shareholder base aligned for the long haul provide resilience.

Valuation and Margin of Safety

Valuing Teqnion is less about spreadsheets and more about judgment. The company is too small, too acquisition-driven, and too decentralized to fit neatly into Wall Street's models. What matters is whether the cash it generates, reinvested at the same cadence and returns, compounds intrinsic value faster than the market expects. That's the lens through which I look at it.

On reported numbers, the picture is straightforward. In 2023, Teqnion earned SEK 7.5 per share. At today's stock price of 145 SEK, that's about 19.3 earnings. On depressed 2024 earnings of SEK 5.58 per share, the multiple stretches to 26. Neither figure screams cheap. But focusing only on the last twelve months misses the point. Earnings power in this business is lumpy because acquisitions close in bursts and macro cycles tug on margins. The real question is what normalized earnings look like over the next five years. If Teqnion rebounds and grows to SEK 10 EPS the stock would be trade at only 14.5x forward earnings. That is the range where wonderful businesses usually sit.

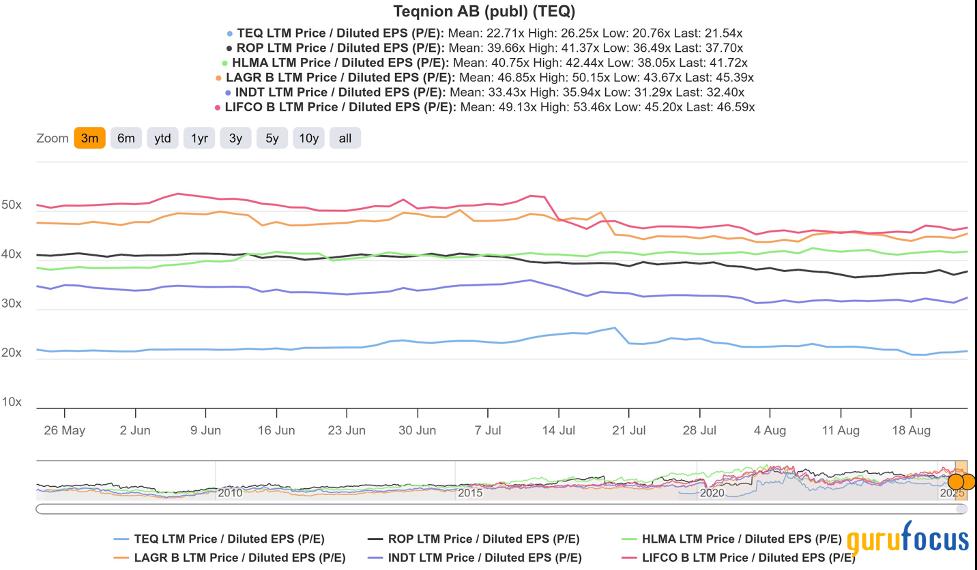

Peer comparisons sharpen the picture. Lifco, Indutrade, and Lagercrantz Sweden's established serial acquirers trade at 32x 47 earnings. Globally, Halma in the UK and Roper in the US fetch similar premiums. By any of these yardsticks, Teqnion is undervalued.

The market is assigning it a junior roll-up multiple when in reality it has proven capital discipline, high insider ownership, and a track record of double-digit compounding. As the company scales, it is not hard to imagine a re-rating that closes part of that gap.

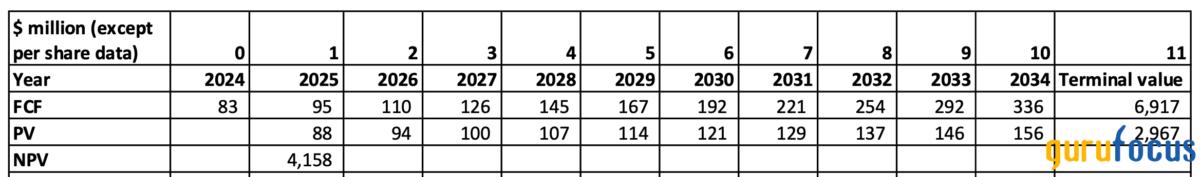

Discounted cash flow provides another lens. Over the past nine years, Teqnion's free cash flow has compounded at an astonishing 22.9% annually. That pace won't last forever, so let's scale it back. Assume free cash flow grows at 15% annually over the next decade, then fades to a 3% terminal rate. Discount those cash flows at 8%, and you arrive at the valuation of nearly SEK 4.16 billion. Against today's valuation, that represents about 43% upside. In other words, even on tempered assumptions, the math points to meaningful undervaluation.

Thus, at current share price, you are paying a good price for a compounding engine that can likely grow value at high double-digits annually. That math still works. If you can hold your nerve through the inevitable bad quarters, the intrinsic value compounding will do the heavy lifting.

Would I Buy the Whole Business?

If I could buy Teqnion outright today for roughly $305 million, what would I own? I would own thirty niche businesses, each with defensible positions in their small markets. I would own $165 million in revenue, $9 million in net profit (depressed), and a pipeline of future acquisitions sourced through a reputation as a permanent home for entrepreneurs. I would own a management team with significant skin in the game, backed by Daniel Ek and Spiltan, and a financial engine capable of compounding double digits for years.

That is exactly the kind of setup Buffett had in mind when he said price is what you pay, value is what you get. Here, I don't think the price is expensive. The value is durable. And the optionality of decades of future acquisitions comes free.

Key Takeaway

Teqnion will never dominate the headlines. It is not in a glamorous sector. But it is quietly building a track record that mirrors the early years of today's great compounders. The market still treats it like a small industrial roll-up. Long-term investors should treat it like what it really is: a capital allocation machine with decades of runway. If your horizon is ten years or more, Teqnion deserves a spot on your short list.