Operators

Introduction

Some operators are used to build expressions returning a result:

- Arithmetic operators

- Comparison operators

- Logical operators

- The ?: ternary operator

- The [] history-referencing operator

Other operators are used to assign values to variables:

=is used to assign a value to a variable, but only when you declare the variable (the first time you use it):=is used to assign a value to a previously declared variable. The following operators can also be used in such a way:+=,-=,*=,/=,%=

As is explained in the Type system page, qualifiers and types play a critical role in

determining the type of results that expressions yield. This, in turn,

has an impact on how and with what functions you will be allowed to use

those results. Expressions always return a value with the strongest

qualifier used in the expression, e.g., if you multiply an “input int”

with a “series int”, the expression will produce a “series int”

result, which you will not be able to use as the argument to length in

ta.ema().

This script will produce a compilation error:

The compiler will complain: Cannot call ‘ta.ema’ with argument

‘length’=‘adjustedLength’. An argument of ‘series int’ type was

used but a ‘simple int’ is expected;. This is happening because

lenInput is an “input int” but factor is a “series int” (it can

only be determined by looking at the value of

year

on each bar). The adjustedLength variable is thus assigned a “series

int” value. Our problem is that the Reference Manual entry for

ta.ema()

tells us that its length parameter requires a “simple” value, which

is a weaker qualifier than “series”, so a “series int” value is not

allowed.

The solution to our conundrum requires:

- Using another moving average function that supports a “series int” length, such as ta.sma(), or

- Not using a calculation producing a “series int” value for our length.

Arithmetic operators

There are five arithmetic operators in Pine Script®:

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

+ | Addition and string concatenation |

- | Subtraction |

* | Multiplication |

/ | Division |

% | Modulo (remainder after division) |

The arithmetic operators above are all binary, meaning they need two operands — or values — to work on, as in the example operation 1 + 2. The + and - can also be unary operators, which means they work on one operand, as in the example values -1 or +1.

If both operands are numbers but at least one of these is of float type, the result will also be a float. If both operands are of int type, the result will also be an int. If at least one operand is na, the result is also na.

Note that when using the division operator with “int” operands, if the two “int” values are not evenly divisible, the result of the division is always a number with a fractional value, e.g., 5/2 = 2.5. To discard the fractional remainder, wrap the division with the int() function, or round the result using math.round(), math.floor(), or math.ceil().

The + operator also serves as the concatenation operator for strings.

"EUR"+"USD" yields the "EURUSD" string.

The % operator calculates the modulo by rounding down the quotient to

the lowest possible value. Here is an easy example that helps illustrate

how the modulo is calculated behind the scenes:

Comparison operators

There are six comparison operators in Pine Script:

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

< | Less Than |

<= | Less Than or Equal To |

!= | Not Equal |

== | Equal |

> | Greater Than |

>= | Greater Than or Equal To |

Comparison operations are binary, and return a result of type “bool”, i.e., true or false. The == equal and != not equal operators can work with operands of any fundamental type, such as colors and strings, while the other comparison operators are only applicable to numerical values. Therefore, "a" != "b" is a valid comparison, but "a" > "b" is invalid.

Examples:

Logical operators

There are three logical operators in Pine Script:

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

not | Negation |

and | Logical Conjunction |

or | Logical Disjunction |

The operator not is unary. When applied to a true, operand the

result will be false, and vice versa.

and operator truth table:

| a | b | a and b |

|---|---|---|

| true | true | true |

| true | false | false |

| false | true | false |

| false | false | false |

or operator truth table:

| a | b | a or b |

|---|---|---|

| true | true | true |

| true | false | true |

| false | true | true |

| false | false | false |

?: ternary operator

The ?: ternary operator is used to create expressions of the form:

The ternary operator returns a result that depends on the value of condition. If it is true, then it returns valueWhenConditionIsTrue. Otherwise, if condition is false, then it returns valueWhenConditionIsFalse.

A combination of ternary expressions can be used to achieve the same effect as a switch structure, e.g.:

The example is calculated from left to right:

- If

timeframe.isintraday

is

true, thencolor.redis returned. If it isfalse, then timeframe.isdaily is evaluated. - If

timeframe.isdaily

is

true, thencolor.greenis returned. If it isfalse, then timeframe.ismonthly is evaluated. - If

timeframe.ismonthly

is

true, thencolor.blueis returned, otherwise na is returned.

Note that, in contrast to conditional structures, the ternary operator does not create local scopes.

[] history-referencing operator

It is possible to refer to past values of time series using the [] history-referencing operator. Past values are values a variable had on bars preceding the bar where the script is currently executing — the current bar. See the Execution model page for more information about the way scripts are executed on bars.

The

[]

operator is used after a variable, expression or function call. The

value used inside the square brackets of the operator is the offset in

the past we want to refer to. To refer to the value of the

volume

built-in variable two bars away from the current bar, one would use

volume[2].

Because series grow dynamically, as the script calculates on successive bars, a constant historical offset refers to different bars. Let’s see how the value returned by the same offset is dynamic, and why series are very different from arrays. In Pine Script, the

close

variable, or close[0] which is equivalent, holds the value of the

current bar’s “close”. If your code is now executing on the third

bar of the dataset (the set of all bars on your chart), close will

contain the price at the close of that bar, close[1] will contain the

price at the close of the preceding bar (the dataset’s second bar), and

close[2], the first bar. close[3] will return

na

because no bar exists in that position, and thus its value is not

available.

When the same code is executed on the next bar, the fourth in the

dataset, close will now contain the closing price of that bar, and the

same close[1] used in your code will now refer to the “close” of the

third bar in the dataset. The close of the first bar in the dataset will

now be close[3], and this time close[4] will return

na.

In the Pine Script runtime environment, as your code is executed once for each historical bar in the dataset, starting from the left of the chart, Pine Script is adding a new element in the series at index 0 and pushing the pre-existing elements in the series one index further away. Arrays, in comparison, can have constant or variable sizes, and their content or indexing structure is not modified by the runtime environment. Pine Script series are thus very different from arrays and only share familiarity with them through their indexing syntax.

When the market for the chart’s symbol is open and the script is executing on the chart’s last bar, the realtime bar, close returns the value of the current price. It will only contain the actual closing price of the realtime bar the last time the script is executed on that bar, when it closes.

Pine Script has a variable that contains the number of the bar the script is executing on: bar_index. On the first bar, bar_index is equal to 0 and it increases by 1 on each successive bar the script executes on. On the last bar, bar_index is equal to the number of bars in the dataset minus one.

There is another important consideration to keep in mind when using the

[] operator in Pine Script. We have seen cases when a history

reference may return the

na

value.

na

represents a value which is not a number and using it in any expression

will produce a result that is also

na

(similar to NaN). Such cases often

happen during the script’s calculations in the early bars of the

dataset, but can also occur in later bars under certain conditions.

If your code does not explicitly handle these special cases using the na() and nz() functions, na values can introduce invalid results in your script’s calculations that can affect calculations all the way to the realtime bar.

These are all valid uses of the [] operator:

Note that the [] operator can only be used once on the same value. This is not allowed:

Operator precedence

The order of calculations is determined by the operators’ precedence. Operators with greater precedence are calculated first. Below is a list of operators sorted by decreasing precedence:

| Precedence | Operator |

|---|---|

| 9 | [] |

| 8 | unary +, unary -, not |

| 7 | *, /, % |

| 6 | +, - |

| 5 | >, <, >=, <= |

| 4 | ==, != |

| 3 | and |

| 2 | or |

| 1 | ?: |

If in one expression there are several operators with the same precedence, then they are calculated left to right.

If the expression must be calculated in a different order than precedence would dictate, then parts of the expression can be grouped together with parentheses.

= assignment operator

The = operator assigns an initial value or reference to a declared variable. It means this is a new variable, and it starts with this value.

These are all valid variable declarations:

See the Variable declarations page for more information on how to declare variables.

:= reassignment operator

The := is used to reassign a value to an existing variable. It says

use this variable that was declared earlier in my script, and give it a

new value.

Variables which have been first declared, then reassigned using :=,

are called mutable variables. All the following examples are valid

variable reassignments. You will find more information on how

var

works in the section on the

`var` declaration mode:

Note that:

- We declare

pHiwith this code:var float pHi = na. The var keyword tells Pine Script that we only want that variable initialized with na on the dataset’s first bar. Thefloatkeyword tells the compiler we are declaring a variable of type “float”. This is necessary because, contrary to most cases, the compiler cannot automatically determine the type of the value on the right side of the=sign. - While the variable declaration will only be executed on the first

bar because it uses

var,

the

pHi := nz(ta.pivothigh(5, 5), pHi)line will be executed on all the chart’s bars. On each bar, it evaluates if the ta.pivothigh() call returns na because that is what the function does when it hasn’t found a new pivot. The nz() function is the one doing the “checking for na” part. When its first argument (ta.pivothigh(5, 5)) is na, it returns the second argument (pHi) instead of the first. When ta.pivothigh() returns the price point of a newly found pivot, that value is assigned topHi. When it returns na because no new pivot was found, we assign the previous value ofpHito itself, in effect preserving its previous value.

The output of our script looks like this:

Note that:

- The line preserves its previous value until a new pivot is found.

- Pivots are detected five bars after the pivot actually occurs

because our

ta.pivothigh(5, 5)call says that we require five lower highs on both sides of a high point for it to be detected as a pivot.

See the Variable reassignment section for more information on how to reassign values to variables.

Compound assignment operators

A compound assignment operator combines an arithmetic operator with the reassignment operator. It provides a shorthand way to perform an arithmetic calculation on a variable and then assign the result back to that same variable.

For example, counter += 1 adds 1 to the current value of a counter variable and assigns the new incremented value back to counter. This operation is equivalent to counter := counter + 1. Note that a variable must be declared before a script can use a compound assignment operator on it.

There are five compound assignment operators in Pine Script:

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

+= | Addition assignment and string concatenation |

-= | Subtraction assignment |

*= | Multiplication assignment |

/= | Division assignment |

%= | Modulo (remainder after division) assignment |

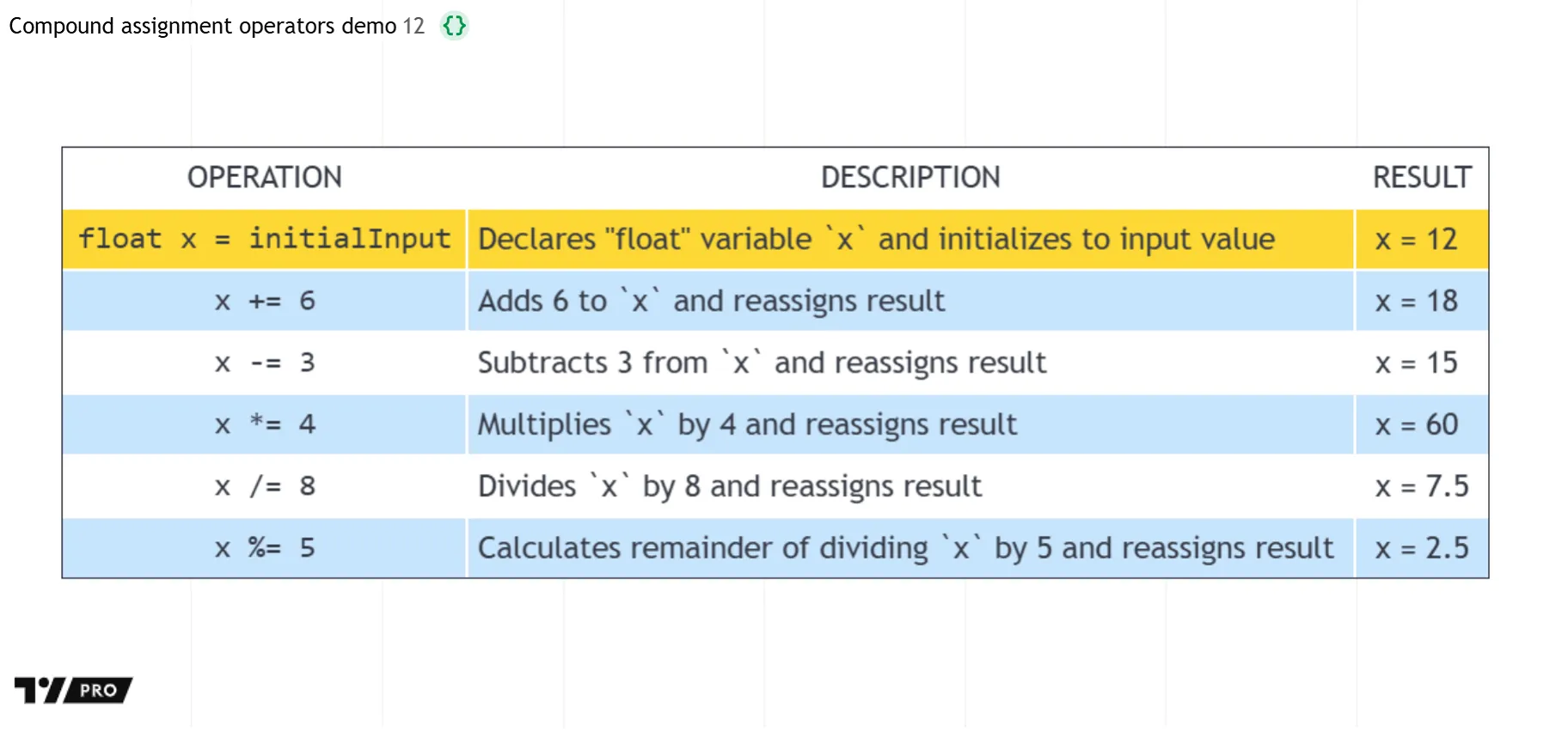

This example executes various compound assignment operations on one “float” variable, x, and traces how each operation changes the variable’s stored value. The script draws a table to show each operation and its resulting value of x after reassignment. A float input can change the initial value assigned to x, which in turn changes the result of each row’s calculation:

The += operator also acts as a concatenation operator when both operands are strings. For example, if a symTicker variable holds the string "NASDAQ:", then symTicker += "AAPL" appends the "AAPL" characters to the "NASDAQ:" characters to create a new “string” value "NASDAQ:AAPL", which is then assigned back to symTicker.